Home / Books / Continent (1986) / The Gift of Stones (1988) / Arcadia (1992) / Signals of Distress (1994) / Quarantine (1997) / Being Dead (1999) / The Devil’s Larder (2001) / Six (2003) / The Pesthouse (2007) / All That Follows (2010) / Harvest (2013)

Set in the early nineteenth century, Signals of Distress describes

the impact on an English coastal town of an unlikely set of visitors and

castaways. Aymer Smith has travelled to Wherrytown on behalf of his family’s

A middle-aged bachelor, Aymer fantasises about

finding himself a ‘country wife’, and is attracted to Katie Norris, a young

newlywed awaiting passage to

Discussion: prisoners of language

According to the author, Signals of Distress, Jim Crace’s fourth novel, is a story of ‘belonging and dislocation’. The people of Wherrytown and the strangers who fetch up in their midst have almost nothing in common with each other. Worse, it seems that no synthesis between Wherrytown and the outside world is even possible; life is organised around states of opposition. ‘The clash of the American and English cultures, the pastoral and industrial worlds, religion and skepticism, capitalism and rural socialism are all played out in this intricately detailed, beautifully realized novel,’ said George Needham in Booklist. Signals of Distress won the Royal Society of Literature’s Winifred Holtby Memorial Prize.

The title ‘signals’ a concern with communication, and one of the book’s themes (I believe) is the failure of human communication to help people cross the gulfs of outlook, sensibility, etc. that separate them. A further opposition to add to the catalogue above might be between abstract and concrete language. (‘Signals of distress’ is a peculiarly abstract way of saying ‘cries for help’ – it’s how Aymer Smith himself would speak.) The errand that brings the central character, Aymer Smith, to Wherrytown in the first place is the delivery of a message. Aymer feels that he has a moral duty to tell the kelpers in person that their supply of sodium ash is no longer required by his family firm. He could have written a letter, but, like many a modern guru of management and human resources, believes that the people deserve to hear it from the horse’s mouth – that a personal communication, ‘face time’ with the boss (or his representative), will somehow make the loss of their livelihood easier to bear. His good intentions are unappreciated, and his clumsy efforts at what is in effect a severance payment are interpreted as charity and proudly rejected. Described at one point as a ‘prisoner’ of his own convoluted, Latinate ‘vocabulary’, Aymer fails to make anything clear, and deludes himself about his own motives.

On the other hand, Aymer’s emancipation of the slave Otto (who seems to have no language at all) is surely a good deed (his ‘one signifying action’, as a reader has called it, in a world where actions speak louder than words). Otto the man disappears; Otto the legend lives on in the racist Wherrytowners’ imagination as a kind of supernatural malevolent force. ‘If anything went wrong – the harvest failed, the yeast went flat, a coin or a button disappeared, they’d say "Otto’s been at work again"…’ Otto thus gives ‘a lasting phrase’ to Wherrytown; wordless, he himself becomes a byword for inexplicable occurrences.

Charles Johnson, writing in The New York Times Book Review (September 24, 1995), praised Signals of Distress for its ‘beguiling narrative ease…superb sympathy… …humour and sparkling prose’. Click here for his review, but be aware that The New York Times on the web does require users to register (it’s free).

The Flying Machine Theatre Company’s adaptation of Signals of Distress opened November 12, 2002, for a three-week run at the SoHo Repertory Theatre, New York. Click here to read the New York Times review.

Click here to read an extract on Signals of Distress from Philip Tew’s full-length critical study Jim Crace (2006).

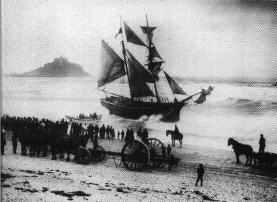

The

photograph that inspired Signals of Distress

In 1888 the Jeune Hortense

ran aground in Mount’s Bay,

© F E Gibson. Permission

kindly granted.

© F E Gibson. Permission

kindly granted.Garrison Lane

Hugh Town, St. Mary's,

Isles of Scilly, TR21

The painting Snowstorm by J.M.W. Turner is used on the cover of the